My Best Rule for Telling Good Art from Bad Art

An invitation to freedom, optimism and new perspectives

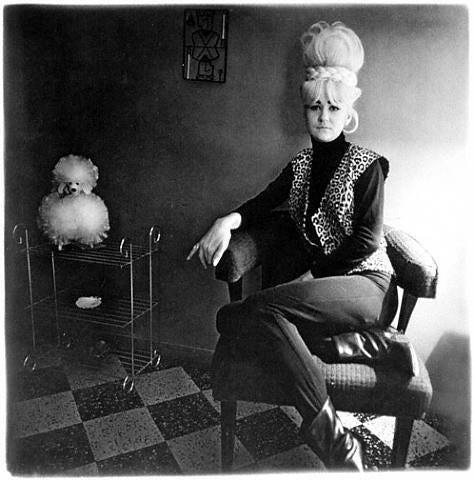

Not long ago, I had a powerful experience at a photography exhibition featuring the work of American photographer Diane Arbus (1923–71).

I didn’t know much about her before I arrived, only that Arbus was a photographer who made intimate black-and-white photos.

What I discovered was that throughout the 1960s Arbus made it her business to take photos of every shade of human life: she took images of circus acts, teenage lovers, penniless kids playing baseball in the park, high-society dames with thick lipstick, transvestites in hair rollers, and everything else in between.

The exhibition was extensive. The full spectrum of human society was depicted. To give you an idea of what was on display, there was one photo with the title “Fat Girl Yawning”. Another was called “Puerto Rican Woman With Beauty Mark”. I was looking at people whose lives were remote from mine, yet my gaze upon them was as intimate as any gaze could be.

There are lots of responses you can have to images like these.

I might have thought about the life of Diane Arbus and the places she had to venture to capture these penetrating snapshots. Or I might have thought about her dedication to the representation of marginalised or hidden people — since these were not the sort of faces you normally find on magazine covers or on TV. Or I could have thought about the interior lives of the people pictured, what they might have been thinking or feeling at the time they posed for Arbus’ roaming camera.

As it happened, I was struck by a more general thought about good art versus bad art: this was good art, and I had absolutely no doubt about it — but it took me some time to realise why.

Expert opinion?

I come to the question of good art against bad as someone who has visited countless art galleries and looked at my fair share of remarkable — and sometimes disappointing — artwork.

Institutional backing tends to throw the question of good art against bad into sharp relief. Public displays of art mounted by an institution, usually with great care and at great cost, tend to carry the implication that the work is good. If a museum is presenting these objects as art, then they must surely possess some merit.

I think of one famous example dating back to the 1970s, when controversy sprang up around the American minimalist sculptor Carl Andre. The uproar came after London’s Tate Gallery used public funds to acquire one of Andre’s works, Equivalent VIII, which consists of a simple rectangular arrangement of bricks laid flat on the floor.

The British press — incorrigibly philistine — were dismayed by the purchase, questioning the use of public money for what was taken to be little more than a stack of building materials. The Daily Mirror carried the front page headline “What a Load of Rubbish”.

Andre’s sculpture was a step too far for the tastes of the British public. The phrase “just a pile of bricks” became emblematic, lingering in the popular imagination as shorthand for the contentious and sometimes dubious nature of contemporary art.

The appeal of rule-breakers

What’s interesting about art history is how many artistic “radicals” who once caused consternation among viewers have since become some of the most well-loved artists in history.

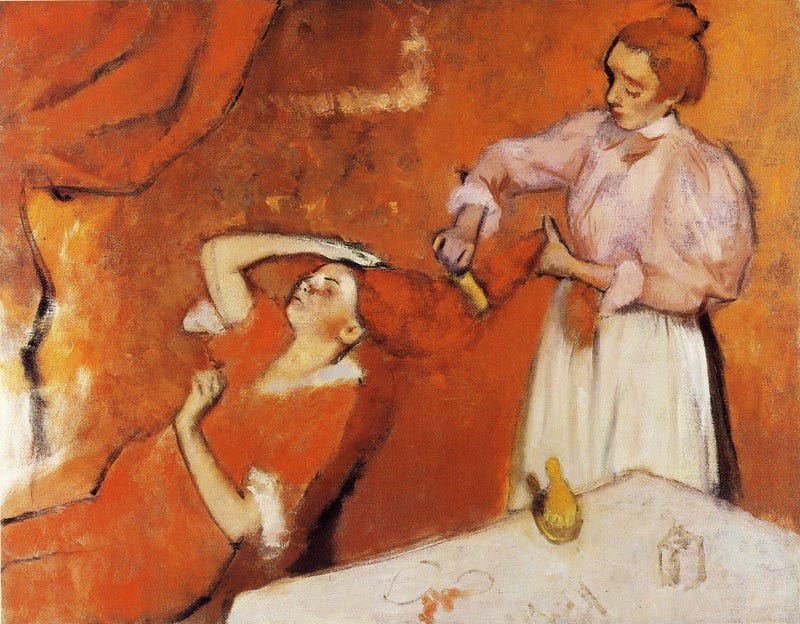

The most striking example of this can be seen in the paintings of the Impressionists, such as those of Edgar Degas and Claude Monet. Although many critics at the time criticised their paintings as too loose and unfinished, their images are now regarded as some of the most beloved works in the canon.

The long list of “isms” — Symbolism, Impressionism, Pointillism, Cubism, Surrealism, and many others — is really a celebration of art that challenged convention but eventually won wide acceptance and admiration.

Such a history should tell us that “taste” — or at least what is deemed acceptable — can and does change. Indeed, with the reappraisal of history brought by relatively new disciplines like feminist, postcolonial, and queer art history, a whole new raft of artists are now being seen and appreciated, when once they were hidden from view.

These worthwhile developments have nothing to do with objective measurements of good art against bad — which I don’t think truly exists anyway — and everything to do with how the river of cultural evaluation winds this way and that, bringing some artists into the light and leaving others in the shadows.

A good test

Given these considerations, it seems to me that the challenge for anybody looking at a work of art in a gallery today is really to be able to decide for themselves whether or not the work is good or not. The challenge, in other words, is to silence the chatter of the wider discourse and to make up one’s own mind.

Here are my thoughts on how to do that.

Consider what the work is doing to your conscious imagination. Does it foster curiosity, sentiment, awe, mystery, puzzlement, shock, and so on?

Consider then if the work converges on a narrow set of such possibilities or if it broadens to a deeper set. Does it lean on you to see things according to a constricted point of view, a tightening of attitudes, or does it prompt a widening — a dispersal, an opening up, a swelling — of perspectives?

This, it seems to me, is a good test as to the merits of an individual work of art.

And that’s what I realised about the photographs of Diane Arbus. Her work was puzzling, provocative, sagacious, and sometimes indelicate but always coming from a place of responsiveness, not an imposition of how or what to think. It opened my eyes to the idea that the world is more interesting and complex than I had previously thought.

That’s why I had no doubt it was good art.

But beyond that, I’ve since realised that good art is less about what meets your eye and more about what it bestows on your imagination. Or to put it another way, borrowing from a quote attributed to Degas and employing it to my own ends, “Art is not what you see but what you make others see.”

I wish you well,

Chris

I’m Christopher P Jones — art writer and book author of How to Read Paintings. You can find out more at chrisjoneswrites.co.uk and my regular blog on Medium.